Why Do Audiences Love Anti-Heroes? A Character Analysis

Posted: May 25, 2023 | Updated: June 13, 2023

Posted In: Articles

For as long as humans have been captivated by traditional hero characters, a love for their equally engrossing, yet variably more complex counterpart – the anti-hero – has existed.

Anti-heroes continue to compel audiences.1 From murderers (Dexter), to drug-dealers (Walter White), to crime family bosses (Tony Soprano), these characters lead some of the most successful shows of the last 30 years. But why?

What is it about these characters that keep viewers drawn to their journeys despite the fact that we’d run the opposite direction if we met them in real life?

Broadly speaking, anti-heroes represent characters that display both moral and immoral behavior. This is why they are often referred to as morally ambiguous characters. They lack the conventional qualities of an established hero, like a strict code of ethics and a desire to do good. Instead, they have much more complex character traits.

In order to understand why audiences love watching anti-heroes on screen, we need to dig into the psychology underlying how we understand other people’s behavior.

The Psychology Behind the Anti-Hero

Unlike traditional heroes who typically embody virtues such as courage, selflessness, and unwavering morality, anti-heroes are morally ambiguous and complicated. They are noteworthy because they possess traits and engage in actions that deviate from what we would do as viewers.

Dr. Clare Grall, Media Psychologist and Research Scientist at StoryFit, has spent a significant amount of time researching this very phenomenon and offering up a dominant explanation and character analysis for it.

Why are we as humans and content consumers so fascinated and interested by characters who do bad things?

One answer, as Grall confirms, lies in the complexity that comes along with moral ambiguity.

“There’s always an out,” she says. “If their motivations are good, it’s not really their fault, is it? It’s not them that’s the problem. They’re simply making the best of bad circumstances.”

Walter White from the infamous series, Breaking Bad, didn’t choose drug dealing, he was forced into it because he wanted to provide for his family after his cancer diagnosis. Dexter Morgan, America’s favorite T.V. serial killer, knows that killing is wrong. He had a traumatic childhood which led him to murderous tendencies, but at least he only kills other criminals right?

In classic psychological terms, we call this an external attribution, when we see the cause of someone’s behavior as out of their control (like taking a detour on your typical route to work because of road construction). You didn’t choose to take a longer route, the circumstances demanded it.

In contrast is an internal attribution, when we blame the person for their decisions – like someone who chooses to bike rather than drive to work when they can.

Making attributions and coming up with explanations for behavior tells us about who a person is and how they interact. “We’re constantly trying to understand why something happened and what will happen next, all of which helps us navigate our social world.”

Importantly, when a story introduces a dynamic character, it’s clear that they have some sense of morality and goodness. Tony Soprano is a main character who obviously loves his family and this is something the audience can relate to.

“We see their good personality traits. That’s what gets the viewers on board with the character,” Grall reiterates, which falls in line with classical lessons from screenwriting text Save the Cat or Affective Disposition Theory (ADT) from media psychology.

As the story unfolds and the character is increasingly faced with novel circumstances. We see the character do something we would never do – like kill someone – and we have better insight into what led to this immoral behavior. And then we’re hooked.

“Our curiosity, our need to minimize uncomfortable ambiguity and have some clear explanation for unfathomable behavior, keeps us coming back to see what happens next.”

Which leads us to our first founding principle as to why audiences love anti-heroes.

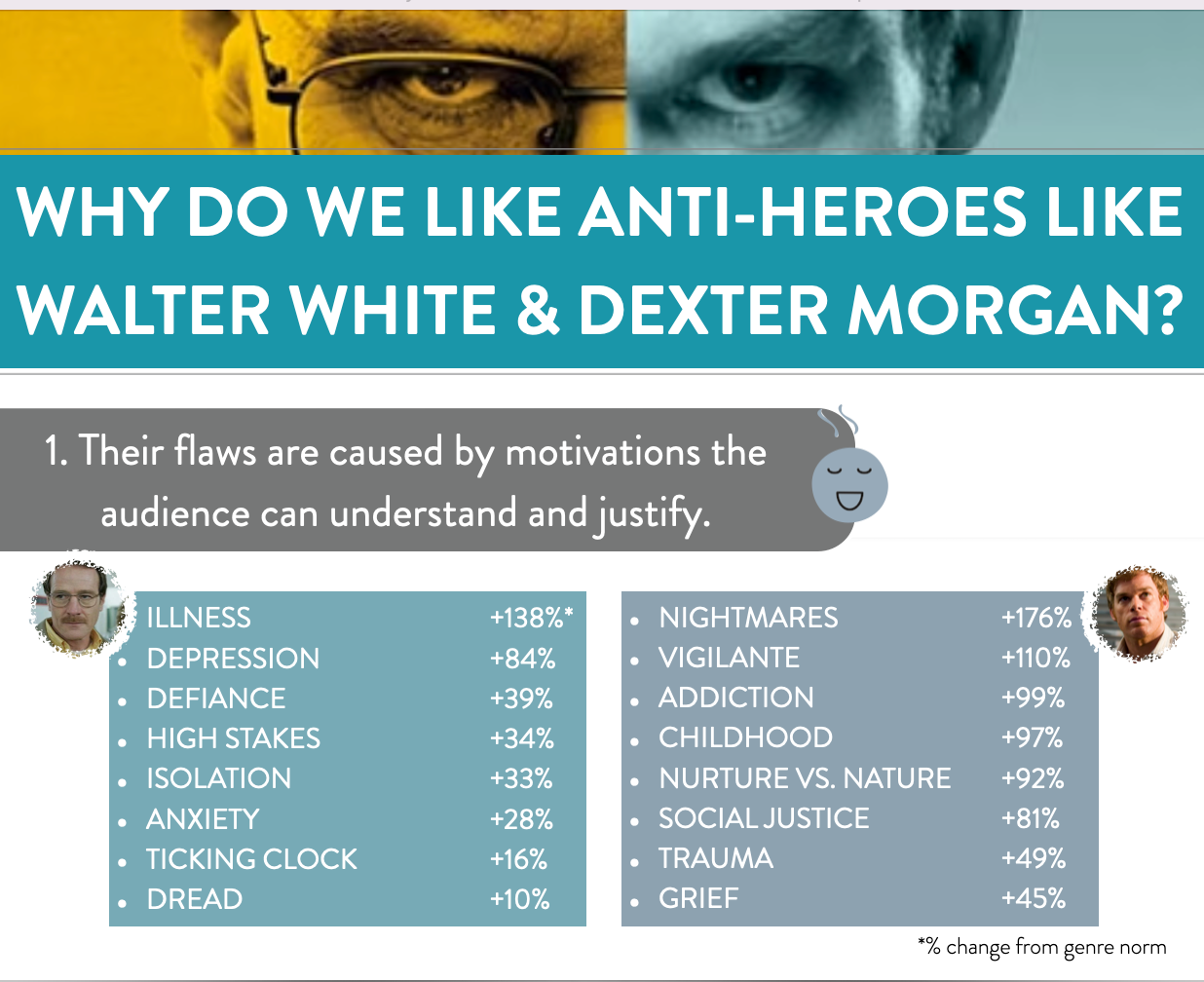

#1 Their flaws are caused by motivations the audience can understand and justify.

Like we mentioned before, anti-heroes are complex.

From a character analysis standpoint, these characters showcase clear and compelling strengths and weaknesses that speak to how they think and behave.

Even when they give the audience reasons to distrust them or question their intentions, their motivations are showcased in a way that viewers can easily empathize with.

Take the character, the Joker for example. Although typically thought of as a villain in the Batman saga, the 2019 origin story adaptation of the classic DC comic, Joker, showcases the static character in a new light.

Audiences are well-familiarized with who the Joker eventually becomes, a criminally insane vigilante who wreaks havoc on Gotham City for his own personal entertainment, but they aren’t familiar with Arthur Fleck, the clown and aspiring comedian.

Fleck is consistently berated in public for being “different,” seemingly a result of a neurological disorder causing him uncontrollable bouts of laughter. He eventually grows to loathe society and the way it treats outcasts.

Events progress from bad to worse and Fleck hits a breaking point. He begins to act out violently towards those he feels have wronged him in the past.

No viewer would deny that his character’s personality is both malicious and immoral, but from this origin story, we can also see what led him to behave this way or why he acts the way he does.

It’s not a justification for evilness, but it opens the door for viewer empathy.

We can all relate to feeling out of place or different – it’s what makes us human. Displaying these kinds of complex emotions from a character that is always painted in a negative light switches up the narrative, effectively making the Joker an evil character with very relatable qualities.

Viewers may be split on their opinions as to whether or not the Joker assumes the role of an anti-hero, but by effectively establishing his backstory in this context, we are less likely to hate him and more inclined to recognize his intrinsic complexity.

Applying the Theory: Walter vs. Dexter

This principle can be applied to many different types of anti-hero leads.

We are all familiar with the story of Walter White: a high school chemistry teacher’s transformation from agreeable underdog into murderous villain.

This dynamic character evolution would not be possible without the catalyst of his cancer diagnosis. That turning point is so meaningful to his story journey that the audience can easily understand and even justify why his character’s role shifts so dramatically and Walt turns to the highly dangerous and illegal business of making and selling meth.

His malicious actions were spurred by holistic intentions (making arrangements to take care of his family after he dies).

Likewise, Dexter’s traumatic childhood and vigilante justification for his “dark passenger” attitude allow the audience to sympathize with his murders — after all, he only kills those that would otherwise be caught by the justice system.

These major characters have become the epitome of complexity because their transformations take it a step further past redemption.

Walt does not stay the underdog who is forced into illegal criminal activities — he actively and consciously chooses to become the villain. Dexter relaxes his rules around his victims to the point where he becomes just like any other serial killer, even manipulating his loved ones to cover for him.

We are so captivated by their actions that when they shift into a villainous role, we are left wondering how we were able to sympathize with them in the first place.

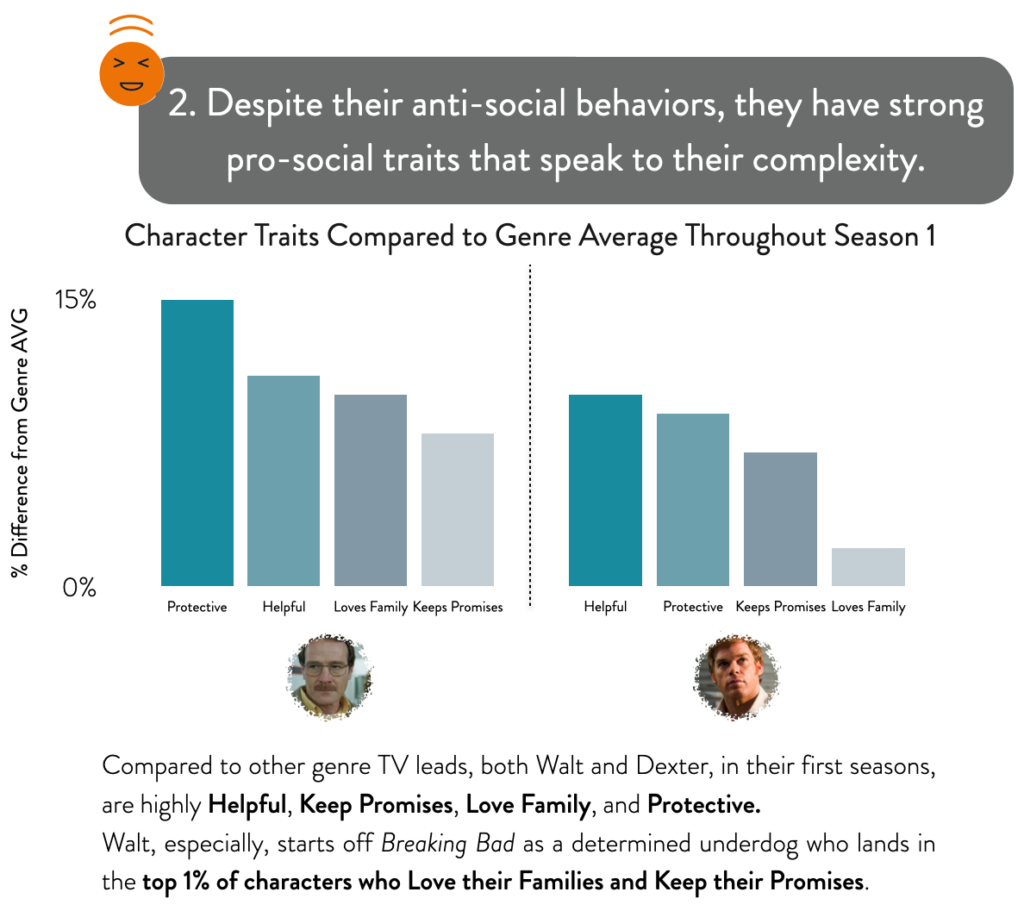

#2 Despite their immoral behaviors, they have strong redeeming traits that speak to their complexity.

Obviously any character that is all bad viewers will perceive as a villain (think Nurse Ratched, Lord Voldemort, Freddie Kruger).

What makes anti-heroes complex is their compilation of traits – both positive and negative – and how they are applied together.

Bolstered by strong prosocial traits that are in stark contrast with their antisocial traits, these characteristics make anti-heroes more compelling.

For example, StoryFit measured these two anti-hero leads to analyze the breakdown of their personalities and unique distribution of pro social vs antisocial traits.

You can learn more about how our AI story intelligence measures character traits and what makes a gold standard character in these StoryFit articles.

In their first seasons, Walt and Dexter both register highly (in the top 10% of all characters in the genre) for Helpful, Keep Promises, Loves Family, and Protective.

Walt begins season 1 as a determined underdog who lands in the top 1% of characters who Love their Families and Keep Their Promises..

In Dexter’s case, his ongoing internal voice-over allows viewers to really know what’s going on behind his facade, making him appear more Authentic and Truthful than he actually may be.

This kind of audience manipulation is intrinsic to their character evolutions.

Dexter Morgan utilizes his pro social traits as a way of establishing a stronger positive connection with his viewers, allowing them to understand his internal thought processes while still getting to fulfill other ulterior motives.

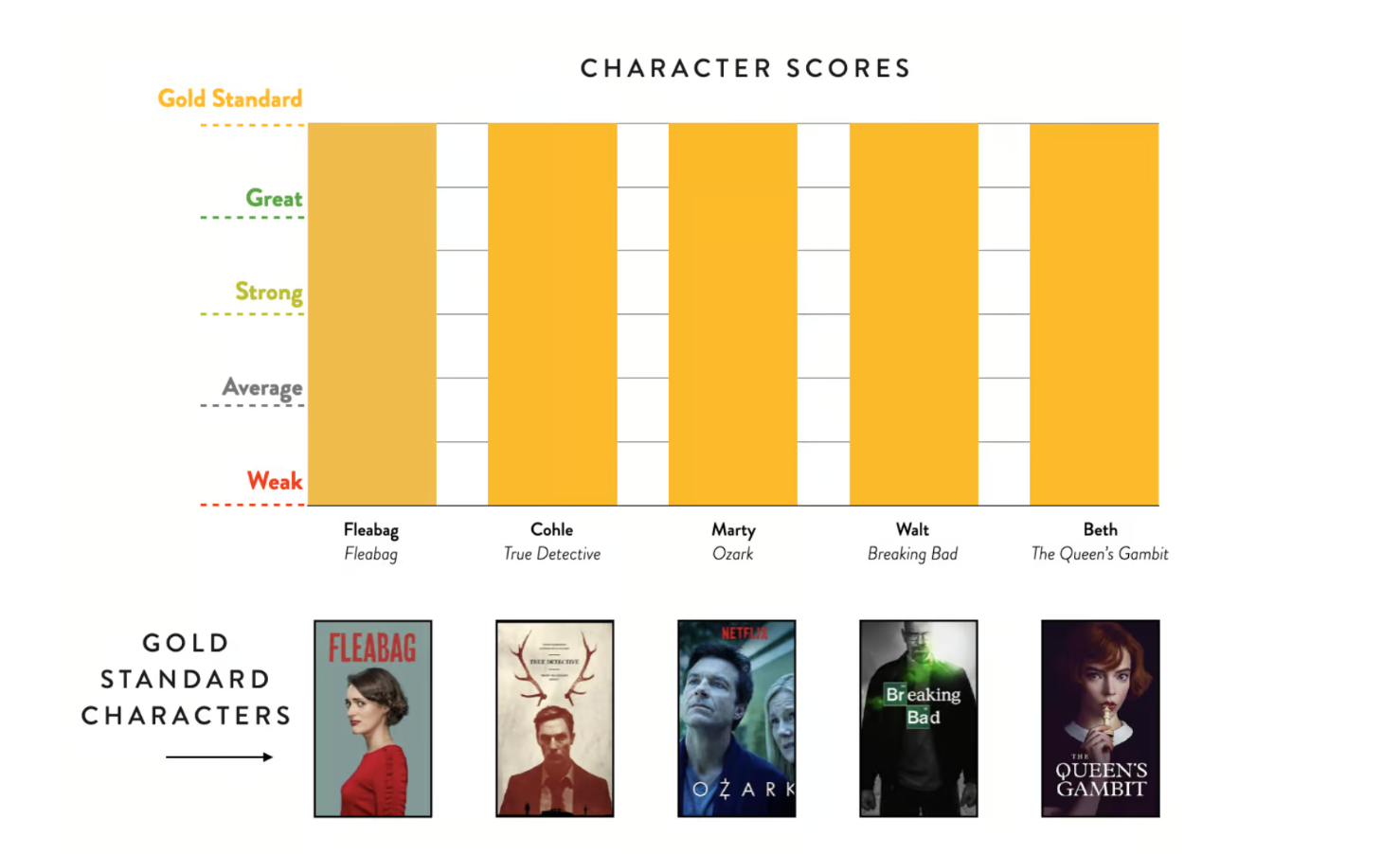

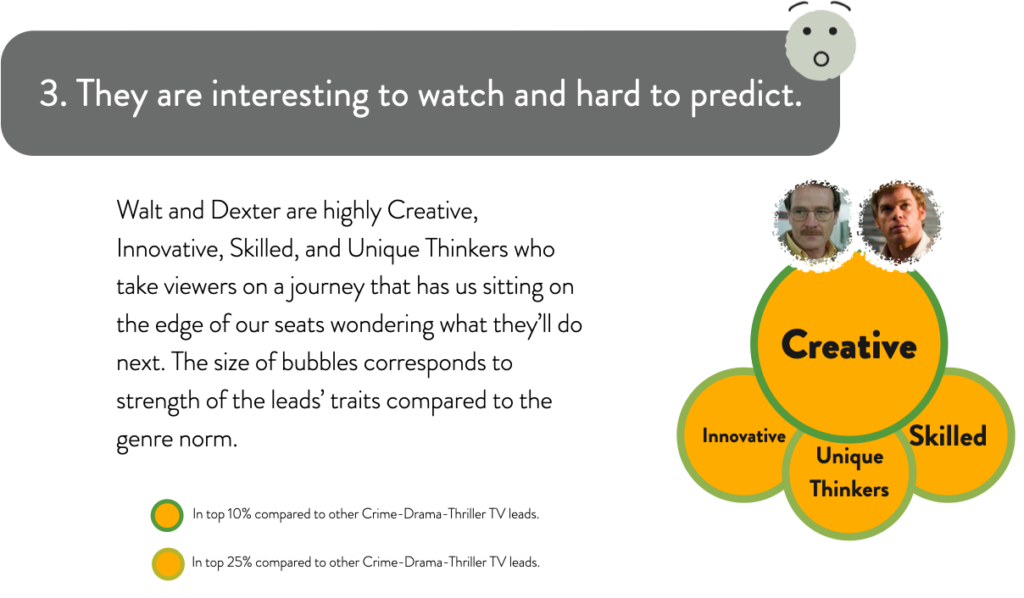

#3 Anti-heroes are interesting to watch and hard to predict.

A complex character can be the signature for a title —their unique combination of traits often makes them iconic or a gold standard character. What do we mean by this?

A Gold Standard Character is one who demonstrates a wide variety of traits and indexes in the top 10% or 25% for several traits when compared against all characters in their respective genre. These characters learn from their experiences and evolve (and devolve) as people, making them both compelling and relatable.

Applying StoryFit’s character analysis tool helps us evaluate the strength of a script’s major and minor characters as well as their character traits.

The character analysis score is an overall indicator of a character’s potential, as our AI engine measures the defining traits that an audience will recognize. Strong characters are the foundation of good stories. A higher score is always better, as this character assessment correlates to the success of a film or series.

Walter White registers as a Gold Standard Character, but he isn’t the only one. They may not all be anti-heroes, but Fleabag (Fleabag), Cohle (True Detective), Marty (Ozark), and Beth (The Queen’s Gambit) all register as iconic leads in their respective story worlds.

Anti-hero characters like Walt and Dexter raise the bar high for character transformation. They are both highly Creative, Innovative, Skilled, and Unique Thinkers who take viewers on a journey that has us sitting on the edge of our seats wondering what they’ll do next.

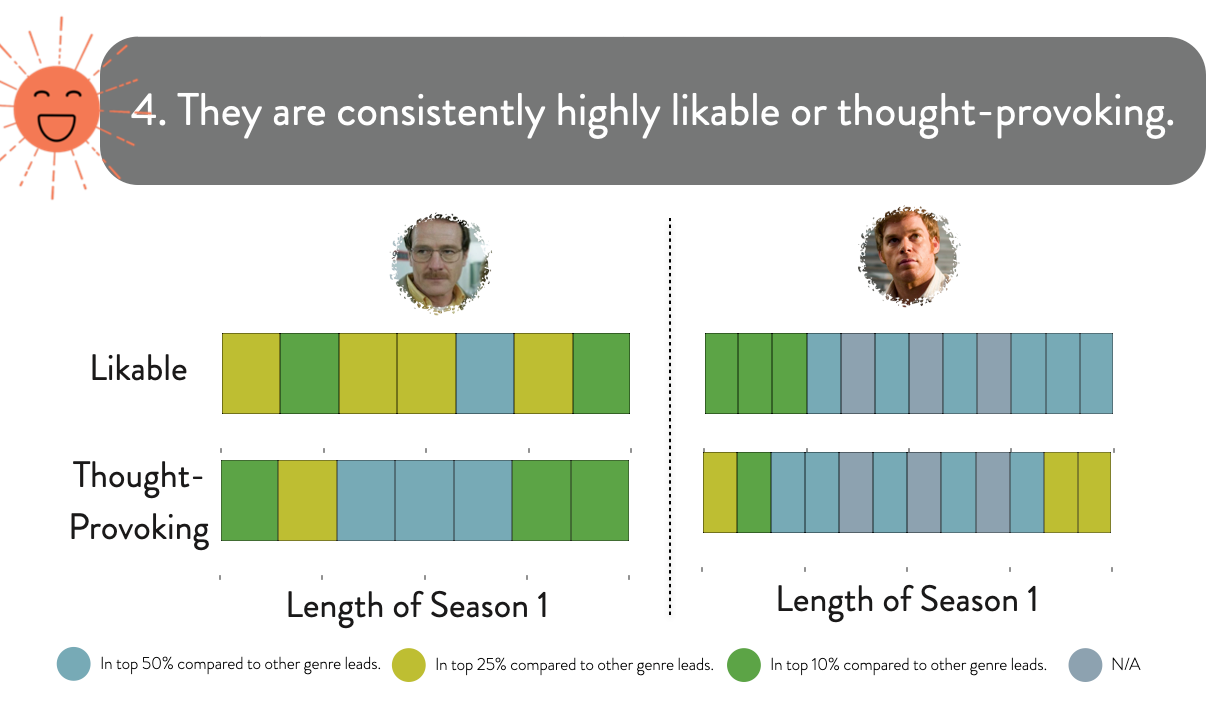

#4 Their mix of traits makes them Thought Provoking and/or more Likable.

Never knowing an anti-hero’s next move is part of the reason we keep following their stories. In other words, the way they keep us guessing makes us want more!

Audience Perception traits are the overall judgements an audience will make about a particular character’s personality.

These traits are essential to the success of any lead because it’s how viewers decide for themselves who these characters are – and how they feel about them.

The three most common Audience Perception traits we look for in a character analysis are:

- Likable

- Interesting

- Thought Provoking

Complex characters like anti-heroes are typically high in at least one Audience Perception trait.

Walt and Dexter, throughout their respective first seasons, are Likable — which offsets audience perception of their illegal activities – and Thought-Provoking, allowing viewers to debate the intricacies of their morally gray actions.

Both Walt and Dexter register in the top 10% for these traits in several episodes of the first season.

Conclusion

Anti-heroes continue to captivate audiences everywhere with their moral ambiguity and complex characteristics – what keeps us guessing keeps us interested!

These leads have distinct and notable flaws, but their character traits are primarily caused by motivations the audience can understand and justify.

Despite their antisocial behaviors, anti-heroes have strong prosocial traits that speak to the complexity of their characters.

They are interesting to watch and hard to predict, and subsequently more likable and thought provoking.

StoryFit’s character analysis delves into the intricacies of their personality traits, pinpointing the reason behind why audiences are drawn to their authenticity, their struggles, and their ability to reflect the shades of gray within each of us.

The anti-hero’s journey offers a refreshing departure from predictable narratives, inviting viewers to question societal norms and explore the depths of human nature.

Ultimately, it is through these flawed and enigmatic characters that we find a reflection and discover a greater understanding of our own inner complexities.

Curious about your story’s anti-hero character? StoryFit can help answer your questions.

Sign up for our newsletter to get all the latest StoryFit news.

References

Wylie, J., Gantman, A. People are curious about immoral and morally ambiguous others. Sci Rep 13, 7355 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30312-9